By Margaret Hedderman

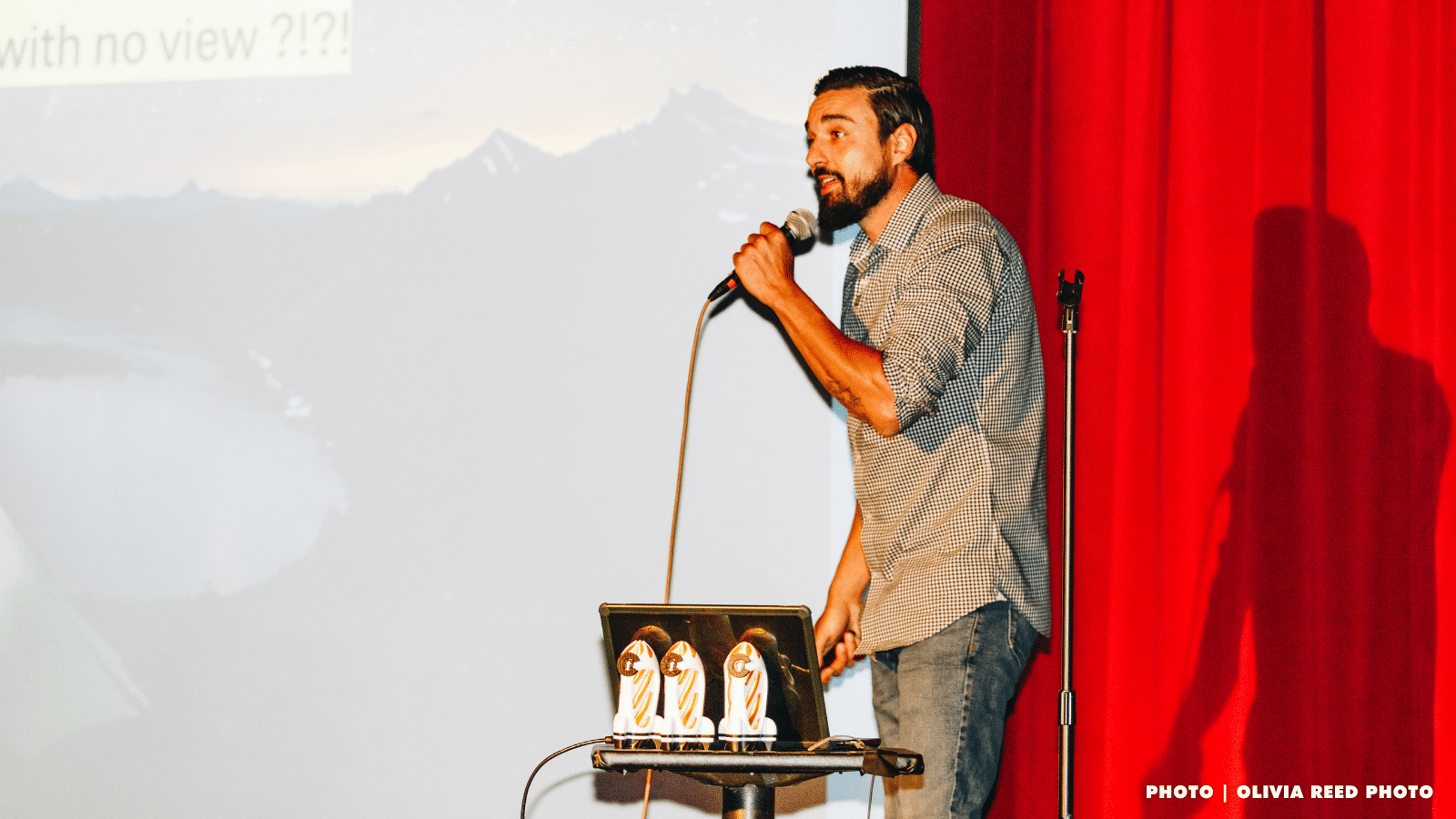

Securing venture capital can feel like a slog for any founder. But for those in rural areas, it often means navigating a system geared toward urban startups with deep networks. Yet, at the Startup Colorado Pitch Competition during West Slope Startup Week, three founders broke through, securing investment deals that could impact the trajectory of their businesses.

What set them apart? How did they capture investor interest and prove that rural startups can compete on the broader market? Today, we’re digging into their journey, uncovering the strategies and decisions that turned their pitches into investments—and what it means for other rural founders looking to fund their business.

UPDATE 🗞️: As of 12/5/24, four founders have secured investment as a result of the Startup Colorado Pitch Competition.

Meet the Winners

Virginia Frischkorn of Partytrick in Basalt — $140K from the Greater Colorado Venture Fund

Partytrick offers a B2B subscription-based, end-to-end platform that simplifies event planning experiences through a streamlined “click, pick, host” process. Designed for businesses, brands, and consumers, the platform serves the $322 billion event planning industry by providing a white-labeled, content-loaded project management tool.

Georgia Grace Edwards of Gnara Apparel in Gunnison — $100K from GCVF

Gnara’s mission is to help everyone “Answer Nature’s Call®” with its patented GoFly® zipper technology, which allows women to discreetly relieve themselves without removing safety gear or exposing skin. The GoFly® zipper revolutionizes women’s outdoor clothing by providing comfort and convenience for activities ranging from hiking to frontline work.

Mark Leonard of ScaleIP in Telluride — $140K from 14 Founders

ScaleIP is a B2B SaaS platform that assists universities, labs, hospitals, and companies in finding high-intent businesses and contacts interested in licensing, selling, or acquiring patents. Unlike traditional patent analytics tools, ScaleIP leverages pioneering intent data to predict which entities are actively “in the market” for IP.

Venture Capital IS NOT where your funding journey begins

Before stepping onto stage at West Slope Startup Week, these founders had already taken significant steps to build their businesses using alternative funding sources. For them, venture capital was a milestone—not the starting point.

“Pursuing alternative funding sources before seeking venture capital is crucial,” says Brittany Romano, Startup Colorado’s Executive Director. “Not only does it show investors that you have skin in the game, but it also helps you validate your product and gain traction on your own terms. By the time you approach VCs, you’ve already proven that there’s market demand and that you can operate efficiently—making you a far more attractive investment.”

Before securing $140,000 from GCVF, Virginia Frischkorn had already pursued a multitude of funding options—all while navigating major shifts in her business model (more on that in a minute). She initially bootstrapped the company, investing significant personal savings and leveraging the financial success of her previous ventures.

“I was lucky I was able to do that,” she said.

Early VC attempts in 2023 were unsuccessful, prompting her to raise approximately $300,000 from her personal network. To stretch her runway, she trimmed her team, pre-sold contracts, and raised another round via family offices before trying the VC route again. Her breakthrough came after she applied for The Pitch Podcast in early 2024, and later the Startup Colorado Pitch Competition.

Another GCVF investment at the pitch competition—Gnara Apparel—also succeeded in sourcing alternative funding prior to securing VC. For Georgia Grace Edwards, her funding journey was built on a diverse strategy that combined crowdfunding, grants, and debt financing. Before receiving an investment from GCVF, Georgia Grace and her team bootstrapped the company from 2018 through 2021, while working full-time jobs or attending school.

“Crowdfunding was the first thing that we relied on,” she explains. Their 2019 campaign through iFundWomen became the highest-grossing campaign in Vermont at the time and funded their initial manufacturing run.

Shortly after, Gnara Apparel (then known as SheFly Apparel), relocated to Gunnison where Georgia Grace and her co-founder won the Moosejaw Outdoor Accelerator Program and secured $50,000 in purchase orders. Shortly after, she won another $100,000 from the MassChallenge Accelerator.

It wasn’t until Georgia Grace pitched at West Slope Startup Week in 2021, that she took the first steps toward VC funding. The following year, she received an initial investment from GCVF, as well as further grants, purchase orders, pre-seed debt financing, and angel investments.

“She’s just an amazingly scrappy and resourceful founder,” said Cory Finney, Partner at GCVF.”

“I think many founders underestimate the time it takes to raise a round of financing,” Cory said.

This can be due to the time needed to build trust with investors, adjust the business model, or navigate external factors beyond a founder’s control. However, both Virginia and Georgia Grace used these extended timelines to their advantage. They refined their strategies, improved their product offerings, and prepared their businesses for future growth, ultimately positioning themselves for successful funding rounds when the opportunity arose.

Virginia, for example, initially assumed Partytrick’s B2C model would be profitable within months, but gaining traction proved slower than anticipated. In early 2023, she decided it was time to raise outside capital as a means of boosting the company’s momentum.

The timing could not have been worse. Silicon Valley Bank collapsed that March, shifting investor sentiment and throwing her plans into disarray.

Virginia described her initial fundraising attempts after the SVB collapse as “a disaster.” Despite failing to secure VC investment, she gained insights that proved invaluable. GCVF was among the early investors who initially declined to get involved.

“The market she was playing in at the time was direct-to-consumer, and we felt there was a larger opportunity on the B2B side,” explained Cory.

The GCVF team encouraged her to shift focus, emphasizing that a B2B model would be more appealing to investors. When Virginia later applied for the Pitch Competition with a refined B2B strategy, it caught Cory’s attention.

“That was really encouraging,” he noted. “We were excited that she devolved the business in that manner.”

Gnara Apparel also faced a major setback just as they were gaining traction. After successfully raising capital through the iFundWomen campaign to pay for their first manufacturing run, the pandemic hit.

“And then we lost everything,” Georgia Grace said. “The factory went out of business overnight.”

Initially, she hoped to qualify for government support, but they were too early-stage.

“At that point, we weren’t like a real company yet—we didn’t have anyone on payroll,” Georgia Grace explained. “So, it’s not like we went out of business because we never really got into business.”

The founders decided to press on. They fronted costs out of pocket to continue working with contractors, secure a new manufacturer, and pursue patent protection.

“We still knew we were on to something,” Georgia Grace said.

With global supply chains still in disarray in 2021, they realized that production delays would continue. So, they chose to focus on education. The team attended two accelerator programs—Moosejaw and MassChallenge—where they learned about wholesale relationships, marketing strategy, and business operations. This investment in learning prepared them to hit the ground running once manufacturing resumed, ultimately refining their brand story and pitch to attract future investors.

It's All About the Relationship

As you may have noticed by now, there’s a recurring theme in these stories: the importance of building solid relationships and trust with investors long before you’re ready to fundraise. It’s not just about having a great pitch or a promising product. It’s about cultivating connections, demonstrating commitment, and allowing potential backers to see your journey up close.

Mark Leonard, founder of ScaleIP, demonstrated the impact of relationship-building with investors well before actively seeking funding. Shortly after launching last November, he raised a pre-seed round through Greater Colorado Venture Fund. He emphasized that this was a direct result of cultivating a relationship with them several months beforehand.

Building relationships during pre-seed rounds is the most important task, he said, and added: “They don’t invest in the company; they invest in the person at that point.”

During this time period, he was also connected with the Kickstart Fund, a VC that focuses on startups in the Intermountain West and operates the 14 Founders program—which eventually invested in ScaleIP at the Pitch Competition. The first outreach was not initially successful.

“We just launched at that point,” Mark said. “So, they wanted us to be a little later stage.”

While Kickstart declined to invest, Mark stayed in touch.

“I kept them in our investor updates and tried to keep a monthly cadence,” he explained, referring to a regular email campaign that investors encourage founders to develop.

These updates allowed the Kickstart team—as well as other potential investors—to see ScaleIP’s progress, even when they weren’t immediately ready to invest. Additionally, Mark made a point to schedule occasional check-in calls with investors to keep the conversation going.

When Mark applied for the Pitch Competition, he did so with a healthy relationship already developed. After the initial application, all finalists participated in several interviews with the competition investors. It was here that he met Harris Cunningham with 14 Founders.

“I saw that they were riding this AI and machine learning wave and it seemed like they were catching it at the right time,” Harris said. “The rate of their adoption was insanely impressive.”

He also observed the relationship that Mark had formed with Matt Smith, a Principal at the Kickstart Fund. To him, the level of trust that had already been developed spoke to the quality of a relationship they might form if an investment was made.

“There’s something about a founder, being able to trust them” Harris said. “It’s like a 10-year relationship from investment to exit.

As you’ve seen by now, securing VC funding is no easy feat, but Virginia Frischkorn, Georgia Grace Edwards, and Mark Leonard have learned a few key lessons along the way. From building early investor relationships to knowing when to pivot, these founders shared practical advice for turning pitches into investments. Here’s their take on how to win over VCs.

Start Building Relationships Early

Mark says that if you’re aiming for rapid growth, venture capital is the right path, but success hinges on building strong relationships well before you actually need funding.

“It’s never too early to start reaching out to them,” he advised, even if it’s just to learn about their investment criteria.

He said that VCs in Colorado and Utah are particularly open to conversations, even if initiated cold. By reaching out early, founders can better understand whether they fit an investor’s profile, saving time and effort in the long run.

“Relationship building is really important,” Mark added, emphasizing that it’s about finding the right match between the founder’s vision and the investor’s expectations.

Investors are People, Too

Virginia emphasized the importance of shifting the traditional power dynamic in fundraising. Early in her career, she made the mistake of giving investors too much power, but she learned to change the narrative: “This is an opportunity that they get to be a part of.”

She said that at the early stages, VCs are ultimately investing in the founder, not just the business model. By approaching investors as collaborators and starting conversations early, she was able to build genuine connections.

“It’s about getting to know people as people,” she explained, which helps potential investors understand and believe in the business, making them more likely to invest.

Ditch the Imposter Syndrome

Georgia Grace’s advice for founders is to overcome imposter syndrome. For her, the key to gaining confidence was realizing, “No one actually knows what I’m doing better than I do.”

While VCs may have broad expertise, she reminds founders that they are the experts in their own ventures.

“Reminding yourself of that,” she says, helps you navigate intimidating and competitive spaces with confidence.

While only three founders received investment during this year’s Startup Colorado Pitch Competition, the other finalists—Robin Hall of Town Hall Outdoor Co, Mike Blecha of AnywhereCam, and Matt Allen of DifferentKind—gained incredible exposure.

“This Pitch Competition was invaluable for every founder who participated,” said Mark Madic, Startup Colorado’s Director of Ecosystem Development and Partnerships. “It provided crucial introductions to investors and gave them firsthand exposure to the VC process. Going through multiple interviews with investors, pitching in front of a live audience, and fielding tough questions—all of it sharpened their skills and prepared them for future fundraising opportunities.”

In the months following the event, Mike Blecha continued the conversation with GCVF and recently announced a $250K investment for AnywhereCam.

DifferentKind also went on to win the TriNet PeopleForceX Pitch Competition in Denver and later announced that they secured additional funding from Fireroad Ventures, Deming Center Venture Fund, and Greater Colorado Venture Fund.

Mark added that pitch competitions are a benefit to rural startup communities. They give founders who may not have had exposure to this process.

“It’s also encouraging for them to see their peers securing significant financing,” Mark said. “This is what fosters belief in rural entrepreneurship. If someone else in a small town can do it, so can they.”

SUBSCRIBE BELOW to stay tuned for our 2025 Startup Colorado Pitch Series, featuring events around the state for entrepreneurs of all levels.